Of course a woman invented the dishwasher

Her name is Josephine Cochrane and I thank her every day. Sometimes twice.

As an author of historical fiction, it’s not unusual for me to go down google rabbit holes about when the term bangs was first used or the history of pockets. At some point, for some reason I cannot recall, I stumbled up the story of Josephine Cochrane, inventor of the dishwasher, and I thought of course. Of course a woman invented the dishwasher.

The story goes that Josephine Garis Cochrane was a nice, middle-class housewife who was annoyed at her household help for chipping her fine heirloom china while hand-washing them. She took on the task herself and, unsurprisingly, found it boring and unpleasant. But dishwashing is a good activity for thinking and at some point, she started thinking about inventing a dishwashing machine. Someone ought to do it, she thought. And when time passed and no one did, she said:

“If nobody is going to invent a [mechanical] dishwashing machine, I am going to do it myself.”

Josephine didn’t have any formal training in engineering because this was the 1800s and she was a woman and schools were only just beginning to enroll them. However, she was the descendent of inventors and engineers (her grandfather invented the first patented steamboat), so she wasn’t completely starting from scratch.

She went to the library and got to work, sketching out a design that would hold plates securely and with wire compartments for cups and saucers. A motor would turn a wheel, pumping hot, soapy water over everything. She worked with a mechanic named George Butters to get a prototype built.

Of getting help from men, she reportedly said:

I couldn’t get men to do the things I wanted in my way until they had tried and failed in their own. And that was costly for me. They knew I knew nothing, academically, about mechanics, and they insisted on having their own way with my invention until they convinced themselves my way was the better, no matter how I had arrived at it.

When her alcoholic husband died, leaving her with little cash and a mountain debts, Josephine’s dishwasher took on a new urgency. She had to make it financially successful in order to survive. I’ve come across this a lot in my research—widows of drunk and debt-ridden husbands are the mothers of invention.

She filed and received her first patent in 1886. She started the Garis-Cochrane Manufacturing Co to make her dishwasher.

But the housewives she’d been intent on helping weren’t buying. For one thing, the machines were expensive, especially for something considered “unnecessary” (probably according to the husbands with the money, not the wives doing endless dishes). Probably more to the point, most people didn’t have hot running water in their homes yet—a requirement for the machine.

In 1893, Josephine displayed her machine at the World’s Columbian Exposition, where it won the highest prize for “best mechanical construction, durability, and adaptation to its line of work.” She started getting attention for her work—and not a moment too soon. She’d been having trouble funding her company and most investors she talked to wanted her to hand over to control to men. A reporter at the time wrote: “I wish that women alone might form the stockholders.”

Her fortunes changed when she made a cold sales call to the Sherman House Hotel in Chicago. This is the part of her story that really slays me:

If you asked me what the hardest part of getting into business was … I think it was crossing the great lobby of the Sherman House alone,” she later told reporters. “You cannot imagine what it was like in those days … for a woman to cross a hotel lobby alone. I had never been anywhere without my husband or father. The lobby seemed a mile wide. I thought I should faint at every step, but I didn’t, and I got an $800 order as my reward.

Can you imagine being brilliant enough to pencil out the design for a mechanical dishwasher, enterprising enough to get it made, patented and form a company to manufacture it but crossing a hotel lobby alone was the hard part? The more I study history and read historical romance, the more I think that the notion of propriety is a trap for women. It’s so insidious and effective at getting women to curtail themselves and police each other. Fuck propriety.

After Josephine landed the Sherman Hotel as a customer, other hotels, hospitals and restaurants followed. Her business took off. Josephine died in 1913, at the age of 74, and her business was ultimately acquired by KitchenAid.

Eventually, the infrastructure was in place to make it possible for families to get a dishwasher at home. But it wasn’t until the 1950s that dishwashers started regularly appearing in most American homes, which feels incredibly recent to me. As much as I love learning about history, it’s inventions like the dishwasher that make glad to live in modern times.

Sources and further reading:

“I’ll Do it Myself” from the United States Patent and Trademark Office

Blast from the Past: Meet Josephine Cochrane, Inventor of the Modern Dishwasher

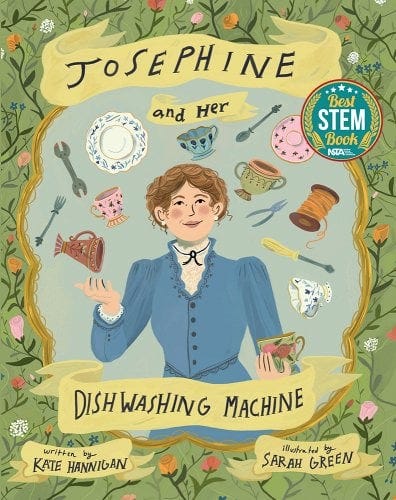

Josephine and Her Dishwashing Machine: Josephine Cochrane's Bright Invention Makes a Splash by Kate Hannigan (Author) Sarah Green (Illustrator).

Maya! Delicious. I'm right with you on propriety. Here's what Soraya Chemaly says in "Rage Becomes Her," which if you have read, you must: "If there is a word that should be retired from use in the service of women’s expression, health, well-being, and equality, it is appropriate—a sloppy, mushy word that purports to convey some important moral essence but in reality is just a policing term used to regulate our language, appearance, and demands. It’s a control word. We are done with control." In my notes, I made it BOLD, ITALIC, & UNDERLINED.

I love this story of Josephine Cochrane. Of course a woman would invent a dishwasher! Why would a man invent a device that could possibly keep women out of the kitchen!