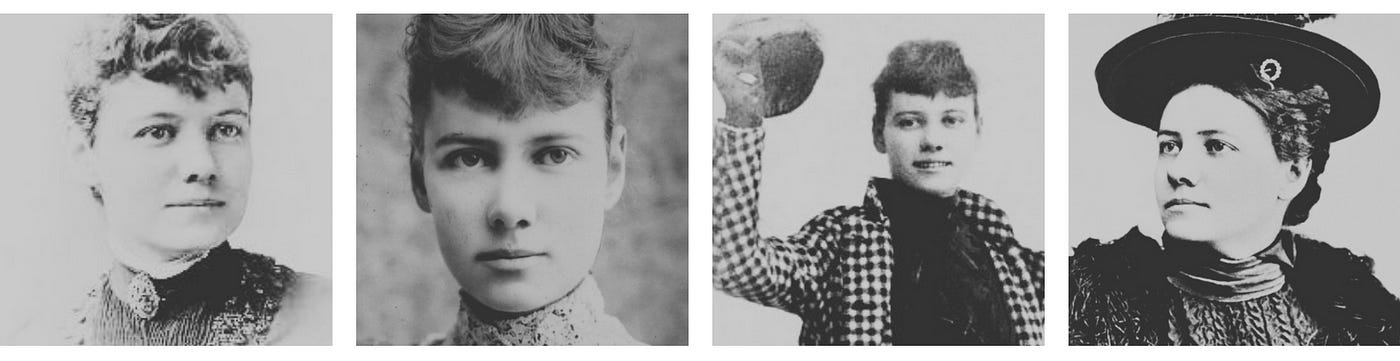

Remembering Nellie Bly

When women’s stories were not deemed newsworthy, Nellie Bly made them sensational.

Nellie Bly is one of my favorite heroines in history and the inspiration for my novel The Mad Girls of New York. This post is in honor of her birthday (May 5, 1864) and was previously published on my website and on this newsletter.

She was the one who put women on the front page of the biggest newspapers in America — in the 1880s. She was the one with her name in the headline, when most male reporters didn’t even get a byline. She arguably invented investigative journalism, with her undercover exposés on conditions for women in insane asylums, factories, and jails. She was the one who raced the fictional Phileas Fogg around the world — and won. Long before Oprah, she was a gifted interviewer, who got the story from her notable female subjects of the day: Susan B Anthony, Emma Goldman, Belva Lockwood and all the first ladies. When she died, one hundred years ago this year, it was said she was the best reporter in America.

Her given name was Elizabeth, her mother called her Pink, but she was and is best known as Nellie Bly.

Nellie Bly was born Elizabeth Cochran in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on May 5, 1864. Her father died unexpectedly when she was young, leaving his wife, Mary Jane and their daughter, Pink (as she was called due to the frilly clothes her mother dressed her in), to fend for themselves. Mary Jane’s disastrous second marriage to an abusive alcoholic followed; at just fourteen Nellie was taking the stand to testify in their divorce proceedings. It is no wonder that young Pink was determined to earn her own way and rely on no man.

But how was a girl in the 1880s supposed to support herself? The one career open to women at the time — teaching — was out of reach, since Nellie couldn’t afford the tuition. The other option was marriage. Fortunately, Nellie lucked into another path.

She got her start writing for newspapers when she penned an outraged letter to the editor of the local paper in response to a father’s despairing letter about what to do with his five daughters. “Gather up the real smart girls, pull them out of the mire, give them a shove up the ladder of life, and be amply repaid both by their success and unforgetfulness of those that held out the helping hand,” Nellie wrote in “The Girl Puzzle.” The editor liked her style, gave her the pseudonym Nellie Bly and she spent the next six years writing for the Pittsburgh Dispatch. She was mostly confined with the ladies pages, though she did manage to file some stories that hinted at her future work, notably an eight part series on female factory workers in Pittsburgh. But even that wasn’t enough to get her off the ladies pages and onto the front page, where she wanted to be.

It seems inevitable that an ambitious, fearless woman like Nellie would take off for New York — and in the somewhat dramatic fashion of not turning up for work one day, leaving only a note that read “Off for New York. Look out for me.” Once in the big city, Nellie had the damndest time getting hired by all the bigshot editors on Newspaper Row; it was generally accepted as true gospel fact that women were too emotional, inaccurate and simply unable to report the news.

But then she talked her way into Pulitzer’s prize newspaper, The New York World, and landed an assignment that would make her career: she was to feign insanity, get herself committed to the notoriously deplorable Insane Asylum for Women at Blackwell’s Island, spend ten days in it’s confines and write about it. Her reply is one for the ages: “I said I could and I would. And I did.”

Her story, detailing the wretched conditions, the brutal treatment of the patients and more than a few perfectly sane women kept against their will was explosive. It lead to an investigation and real change.

Nellie had found her beat. Or rather; she had invented it.

Nellie would go off in disguise to report on a story, which often focused on the lives and experiences of working women who were chronically ignored and overlooked. From 1887 to 1890, Nellie exposed an Albany lobbyist, got arrested and spent the night in jail, explored the black market for babies, worked in a hatbox factory, and learned ballet. She almost got her tonsils removed during a visit to the dispensary (clinics in lower income communities) in a stunt that nearly went too far.

No matter the topic, Nellie always inserted herself in the story. “Did I think I had the courage to go through such an ordeal as the mission would demand? I said I believed I could.” In her gripping account of Ten Days in A Madhouse she describes the extensive horrors she witnesses — as well as handsome doctors, the state of her bangs and her “chronic smile.” On the idea for her around the world stunt: “I need a vacation; why not take a trip around the world?”

Her stories were so incredibly popular that other papers hired their own lady reporters to file similar articles and thus the era of the stunt girl reporter was born. Women like Winifred Black, Nell Nelson, Eva McDonald and others filed stories about female factory workers, trying to get abortions, or women’s treatment at public hospitals. Nellie and the other stunt girls proved wrong all those stuffy male editors who said women couldn’t get the news and they did so in a spectacular fashion.

We call it “stunt girl” reporting now, but that cuteness hides how subversive it really was. The stunt was only ever the hook; what made the work truly sensational was the way it brought to life and made us care about the lives of women who were otherwise ignored or overlooked. The mad women locked away, the poor women working for meager wages, the women desperate to give away or get a baby. These journalists crafted a new image of womanhood and got it on the front pages of the biggest papers in America, devoured by readers, obliterating the old maxim that a woman should only appear in the newspaper on the occasion of her wedding or death. The stunt girl reporters got their foot in the newsroom door and shoved it open, so generations of female journalists could follow. Recently, women led the newsrooms at The Washington Post, Reuters, ABC News, CBS News, USA Today, The Economist, The Financial Times, NPR and others. We can draw a line directly from Nellie Bly’s work to their modern day opportunities.

OnNovember 14, 1889, Nellie embarked on her greatest stunt yet: a solo trip around the world in a bid to be faster than the fictional record in Jules Verne novel Around the World in 80 Days. When the idea first surfaced in the World newsroom, the editors planned to send a man. After all, a woman couldn’t possible go alone! She’d have too much luggage!

Had they not met their co-worker, Nellie Bly?

Nellie told them to send a man and she’d race him — and win — on behalf of a rival paper.

They sent Nellie.

She had two day’s notice to prepare, and she packed just one suitcase. And then she was off — hitting up England, France, Egypt China, and Japan. Elizabeth Bisland, a reporter for Cosmopolitan (yes that Cosmopolitan) set off in the other direction to race Nellie. Because of course women had to be pitted against each other for copy. Nellie, unaware, kept up with her travels and filing stories (Some, in must be said, with some unacceptably racist depictions). Back home, the editors whipped readers up into a frenzy with breathless updates, sweepstakes and contests to guess the time of her return. When Nellie embarked on the final leg of her journey, a train ride from San Francisco to New York, there were crowds cheering her every step of the way.

She made it back to great fanfare, in just 72 days.

When Nellie returned, she was absurdly, impossibly famous. Possibly even too famous to go on as an un undercover reporter, now that her likeness was emblazoned on board games and other merchandise. And when the World didn’t pay her what she thought she was worth after such a blockbuster story, she quit. (To quote feminists today: “Fuck you, pay me.”). The era of Nellie Bly as stunt girl was over, but she wasn’t done yet.

For her next act, Nellie wrote novels, which she was very bad at but was paid a lot of money for. She went back to reporting and demonstrated that she wasn’t just a one trick pony; she had a knack for interviewing people. Once again, she used her platform to highlight other women: she interviewed Susan B Anthony, Emma Goldman, Belva Lockwood and others. Her coverage of the Pullman Riots was highly regarded. She started covering the Suffrage movement, too.

Nellie then did the storybook thing where she married a millionaire. Her husband, Robert Seaman was a wealthy industrialist forty years her senior. After a rocky first year of marriage, they seemed to forge something of a true partnership in both home and business. When he died, he left Nellie ownership of his manufacturing company. She was already heavily involved, even inventing and patenting a new design for a barrel (as one does). In the spirit of the Progressive Era (and being a decent person) Nellie instituted many benefits, like a gymnasium, kitchen and various social and literacy clubs for the company’s employees. This, in a time when factories still locked the doors preventing their workers from escaping during the day, and even during fires.

But an office romance with a top executive — after her husband’s death — may have blinded her to some nefarious financial dealings behind the scenes that tanked her business, led to years of litigation and eventual bankruptcy.

On being a woman in business, Nellie had this to say:

They tolerate us women now down in the clerical classes, but when we try for anything more, why we get ahead only so far as we can fight our way against obstacles from which a businessman, with the prestige that surrounds his success, is entirely, or almost entirely free.

In 1914, Nellie was broke and at odds with her family. She set sail for Europe, only for World War One to break out. So she did her thing: she got the story. At this point in time, the story to get was from the front and so that’s where Nellie went. After the war, she returned to New York where her old friend Arthur Brisbane, hired her to write a column for The New York Evening Journal. A large focus on her columns became uniting orphans with forever homes. Once again, she was drawn to the stories and experiences of women and children and made everyone else care about them too. They way she used her platform to champion women and children is one of her greatest legacies.

The qualities that earned Nellie that platform are another legacy that Nellie leaves us, and it’s why she’s so captivating to women and girls — once they learn about her. Call it pluck, grit, gumption, call her a daring girl or rebel or whatever — Nellie Bly was unapologetically confident. She had to be, tell off an older male newspaper editor as a teenage girl! She had to be, to attempt the dangerous stories and boundary-breaking career she did (“What, like it’s hard?). She had to be, in the way she put her body on the line and herself in every story. It’s there, in the way she centers herself in the story without apology. Women can be plagued with imposter syndrome, made to fear stepping out into the world, made to worry about how they present themselves, made painfully aware of double standards and tightropes they have to walk (backwards, in heels!). Nellie had all that too but she just…burst past it.

In her own words: “I always have a comfortable feeling that nothing is impossible if one applies a certain amount of energy in the right direction.”

Nellie Bly died of pneumonia on January 27, 1922. On her passing, famed newspaper editor Arthur Brisbane called her “the best reporter in America” and wrote:

Her life was useful and she takes with her from this earth all that she cared for, an honorable name, the respect and affection of her fellow workers, the memory of good fights well fought and of many good deeds never to be forgotten by those that had no friend but Nellie Bly. Happy be man or woman that can leave as good a record.

PS: I wrote about Nellie Bly’s first big sensational story in my novel, The Mad Girls of New York. Check it out!

Have you been to Miss Nellie's on West 44th Street? It's a restaurant that is named after Nellie Bly.

Thank you for inspiration in so much. ❤️