Spectacle and Scandal! The true story of the Women's March of 1913

What we should be talking about when talk about the 1913 Women’s March

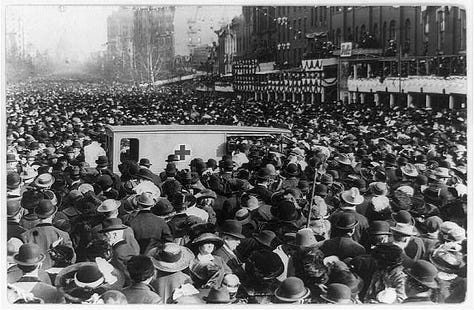

On March 3, in the year 1913, the Suffs majorly trolled the incoming president. The story goes that when Wilson arrived in Washington for his inauguration, scheduled for the next day, he stepped off the train and onto an empty platform. “Where is everybody?” he asked. The answer: they were watching the Suffrage parade.

This wasn’t just any parade—it was an extraordinary and extravagant display of women’s determination to get the vote. Nearly ten thousand women had traveled to Washington D.C. to march in the parade. There were twenty-six floats, six golden chariots, ten bands, forty-five captains, two hundred marshals, six mounted heralds and six mounted brigades. Women marched in groups—as nurses, journalists, homemakers, college students, by state of residence. Even men joined in. The beautiful Inez Milholland led the way on a white horse, reclaiming the image of a knight.

There were thousands of women marching behind the “Great Demand” banner which boldly declared: We demand and amendment to the constitution of the United States enfranchising the women of this country. It was the first time women had used such plainly strong language to say what they wanted.

It took months of organizing, led by Alice Paul. Though she was Pennsylvania Quaker, she was new to the American Suffrage fight, having spent the past few years studying in England. While she was studying abroad, she fell in with the radical, militant Suffs led by the Pankhurst mother/daughter team. She controversially brought their radical methods back to the States.

Alice persuaded the National American Association of Women’s Suffrage (NAWSA) to let her plan a stunning parade. They gave their reluctant support, list of members she might contact (most were dead) and some official NAWSA stationary. She was on her own to fundraise, assemble a team and orchestrate every last detail.

There was a whole kerfuffle about getting the permit—The chief of police, Major Richard Sylvester, kept refusing a permit for that avenue on that date. He suggested other days, other streets. But Alice was adamant. She planned as if she would be successful. Ultimately she succeeded by going around him (predating Tina Fey’s famous advice for women to go Over! Under! Through!). A committee of wives of congressmen got involved and lo, the parade permit was obtained for the desired date and route. But Major Sylvester refused to provide adequate police protection—which would prove to be dire.

There was also the matter of whether or not to include women of color in the march. One of Alice’s co-organizers had recruited women from Howard University to march in the college section, where Alice herself was planning to march. Someone pointed out that having Black women join the march in a Southern town, on the eve of the election of a Southern president might not be a good idea. Rumors started flying—will Black women be encouraged or allowed to march or not? Were they welcome or not? It was said there was a risk of of losing financial support; however it should be noted that one of the main financial backers of Alice Paul’s efforts Alva Belmont, who also funded Black suffrage organizations and efforts in New York City.

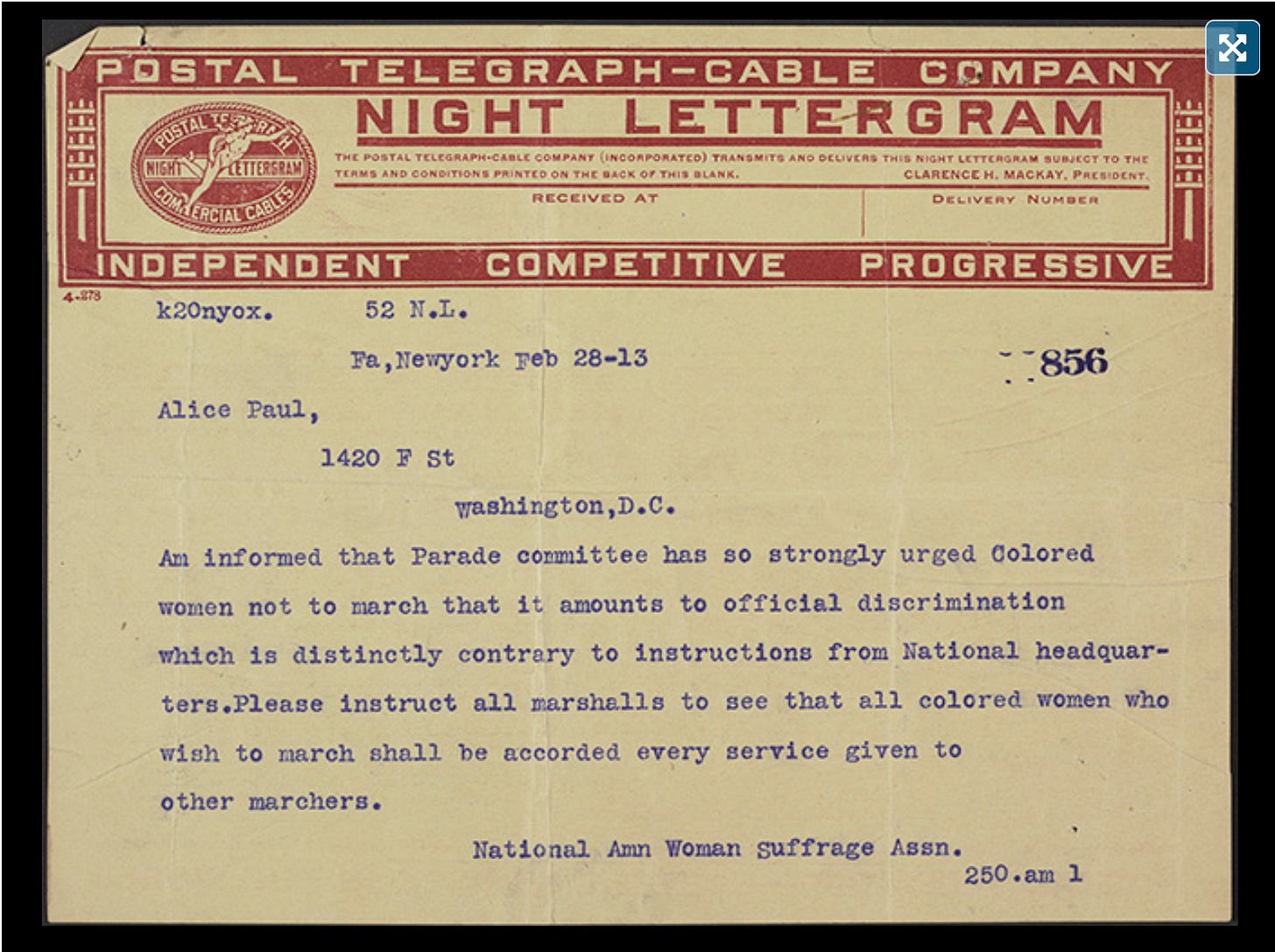

Either way, Alice apparently waffled and tried to please everyone. Rumors flew. Attempts were made at damage control. NAWSA Headquarters got wind of this and issued the following telegram:

It reads:

Am informed that Parade committee has strongly urged colored women not to march that it amounts to unofficial discrimination which is distinctly contrary to directions from National Headquarters. Please instruct all marshalls to see that all colored women who wish to march shall be accorded every service given to other marchers.

However, that didn’t mean that Black women didn’t experience racism when it came to this parade. According to a factsheet from the Alice Paul center:

They were not included in parade organizing committees, despite black participation in other marches in the northern states. Their input was not initially sought when questions arose about black women participating in the parade.

One of the most famous stories about this march involves the visionary Suffragist and journalist, Ida B. Wells. She was planning to march with her state delegation, but was then instructed not to. On the morning of the parade, her fellow Illinois Suffs were wondering: where was Ida? She wasn’t the sort to accept such injustice. The story goes that she waited along the route to join the parade, where she proudly marched with her state delegation. This story suggests that she alone rebelliously joined the march. Yet it’s not the whole truth.

In her book Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote and Insisted On Equality For All, historian and author Martha S. Jones presents a different picture. Many black women marched alongside the others. Jones includes a long list of notable Black women there, including Mary Church Terrell, a contingent of college women including Anna Evans Murray and many Howard university students in cap and gown. Sculptor May Howard Jackson was there, drug store owners Dr. Amanda Gray and Dr. Eva Ross. She notes that at least three black women marched with their state delegations. She also quotes a contemporary journalist as saying:

“No color line existed in any part of it. Afro-American women proudly marched right by the side of the white sisters.”

In the end, white and black women came together and marched together and hundreds of thousands of people turned out to watch them. Why isn’t this true story the one we tell when we talk about this march (if it’s talked about at all)?

It has become fashionable to say that the Suffs were just racist middle class white women and to write off the whole movement because of it. It has become fashionable to say that the 19th amendment only gave white women the vote (fact: the language in the Constitution gave all women the vote, but Southern states immediately applied their old tactics to disenfranchise people of color). The truth is, there are examples of outrageous racism on the part of the Suffs. But there are also many, many examples of women and men collaborating across class and color lines to fight for women’s suffrage.

We have to ask: who is served by this legacy of division?

Answer: anyone who is threatened by independent, empowered women and people of color benefits from those groups squabbling amongst themselves. The truth is, together there are more of us than there are of them and we are a powerful block when we are united together. No one can go back and change the history—but one can erase the truth or tell stories that deliver the wrong lesson. We need to be careful not to perpetuate a narrative of division. We need to tell the true stories that reinforce our alliance, not the versions that try to divide us.

The real scandal about this march, if you ask me, is that the bystanders—mostly men—went rogue and went on the attack. Literally. Women marching peacefully for their rights in 1913 were verbally attacked and brutally beaten in the streets. The women bravely fought off the men with banner poles and hatpins. They marched on even when the mob overran the streets and forced them to go forward single file.

The police present did not do much to help—the exception being the African-American police officers who were the only ones to step in between the mob and the marchers. Jones quotes a Suffragist marcher saying:

“As I went along I noticed the policemen, as a rule, stood quietly. There was very little said or done. But the only efforts really actively made, as I happened to notice, were by this colored policeman.”

There weren’t many police because of Major Sylvester’s refused to deliver additional police protection. The boy scouts he sent instead were not quite up to the task of holding back an unruly mob of grown men. In the end, they literally had to call in the calvary to stop the violent mob of men so the women’s peaceful march could continue.

All their beautiful costumes and banners were trashed. Their months of careful planning was trashed. Women were sent to the hospital by the dozen—with injuries inflicted by “women’s protector.”

But this happened in the new era of photography and those pictures were on the front page of the newspaper the next day. It is said that the images of nice, proud, respectable women under attack by the nation’s fathers, brothers and sons did more to turn people in favor of women’s suffrage than any of the arguments Suffs had made over the years.

When I think about this march, the truly scandalous story is how men attacked peaceful women protestors of all colors because the women wanted to live in a democracy in truth, not just in name. This is what we should be talking about when we talk about the women’s march of 1913. We should be talking about it today.

Oh yes, we should, and all thinking people are. I would wish for all of us to remember that the reactivity needed to stop these American oligarchs is slowly but surely happening. In as much as it would be so cool for a large, swooping gesture that would stop them in their tracks, that's not really how change works. It works one-by-one, small action by small action, slowly accumulating momentum until critical mass occurs. That day is coming. Sisters and brothers who believe in democracy, remember that "all" Rosa Parks did was sit down. Where are you going to follow her lead? And, Maya, once again, I have a heart full of gratitude for your courage in writing and disseminating stories like this one. Brava!

Thank you for reminding us we are better together, stronger than we think.