The Matilda Effect

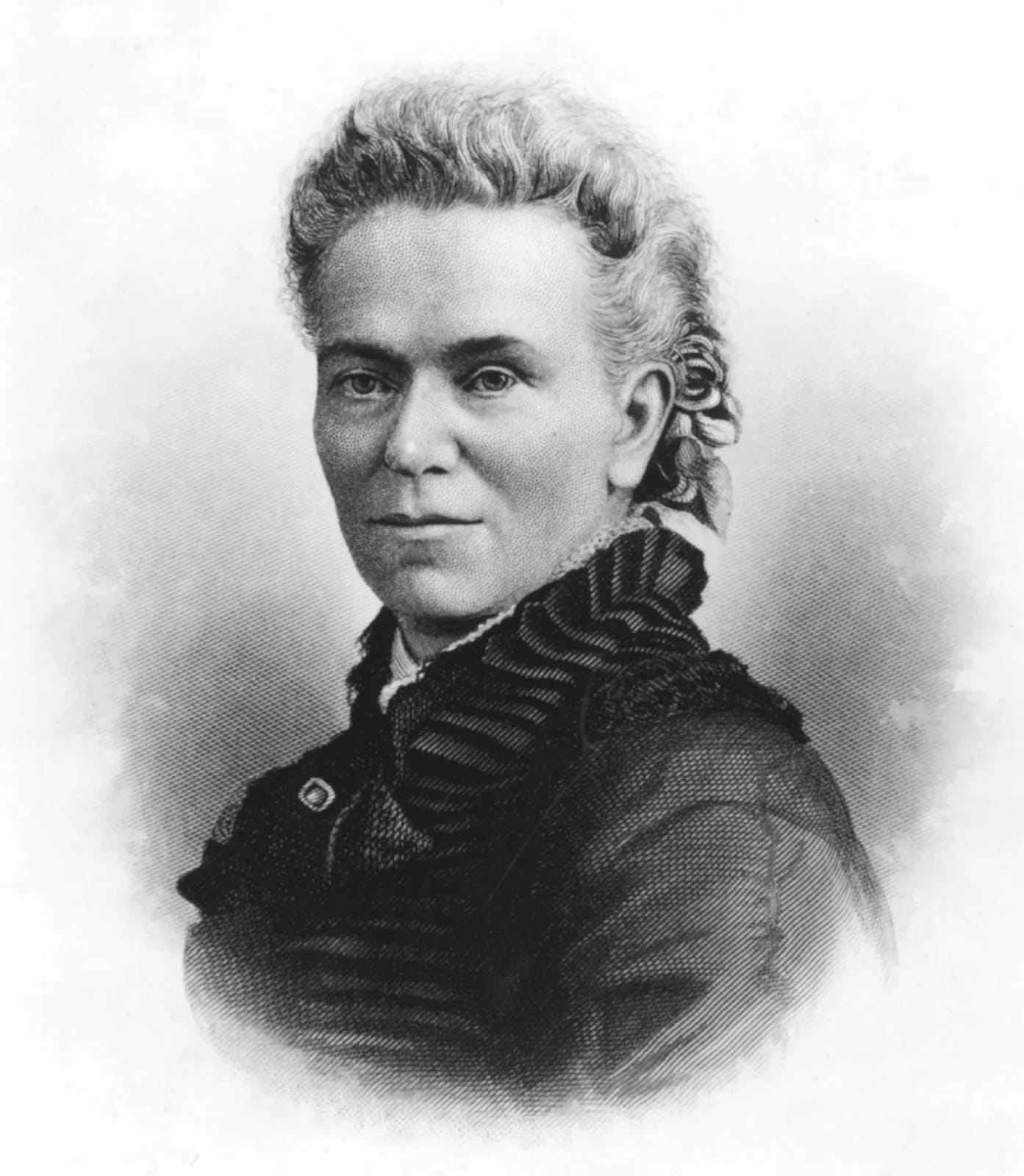

Matilda Joslyn Gage and why we need women’s history month

It’s weirdly, devastatingly appropriate that many of us don’t know about Matilda Joslyn Gage, after whom the Matilda Effect is named. Maybe a lot of us don’t even know about The Matilda Effect (I only learned about it, oh, last year) even though I think we are all vaguely aware of it, if not by name, at least by its definition.

The Matilda Effect is a bias against acknowledging the achievements of women scientists whose work is attributed to their male colleagues.

But I think we can apply the Matilda Effect to women’s history too. Consider it a bias against acknowledging the achievements or even existence of women in history.

Consider the life of Matilda herself. She was one of the most radical thinkers of the 19th century on abolition and women’s rights. She was part of the triumvirate leading the women’s suffrage movement (alongside famous besties Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton). She inspired one of the most beloved children’s stories of all time. And she was remarkably prescient about “the dangers of the hour” that we are facing once more today.

Matilda Joslyn Gage was born to parents we would consider progressive today. They were abolitionists and they believed in encouraging their daughter’s curiosity and education. She was allowed to stay up late when guests came over and participate in the adult conversation. Her mother enjoyed enjoyed historical research and taught her daughter.

When young Matilda wanted to be a doctor, like her father, she studied and trained for it as much as she could. Her father wrote to medical schools seeking a spot for her. The answer was always no. She decided to change the rules so that other women would be able to enjoy opportunities denied to her.

She married Henry Gage, a like-minded reformer, and she became a mother. But wifedom and motherhood did not consume her; Matilda never gave up thinking, learning, writing or engaging with the world. For this post, I picked a few moments from her long and full life that stuck out to me as deeply relatable and also illustrative of her life and work.

“The question is, how can this mental and moral lethargy, which now binds the generality of women, be shaken off?” —MJG

Matilda discovered the women’s rights movement when reading about Seneca falls in the newspaper after the birth of her second child. She avidly followed the movement via the press for years—perhaps feeling, as I did, radicalized after becoming a mom. Years later, in 1852, she finally was able to attend a convention. She took her seven year-old daughter with her. When she stood up to speak she was so nervous that she was trembling. But she held her daughter’s hand through all of it, drawing strength from her.

Matilda talked about “shining examples” of what women in history had already achieved. It was extremely well received and had women asking “why had they not heard of the women she described? Her ideas made them question how they were taught history.”

With this speech, Matilda quickly distinguished herself and became part of the inner circle leading the movement—Matilda was working closely with famous besties Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony every step of the way. Sometimes I get a “third wheel” vibe but I can also see how Matilda must have connected with them both. She was just as unapologetically radical as Elizabeth, especially when it came to the Church’s subjugation of women. Like Susan, she was also an excellent organizer, lecturer and worker. Matilda organized conferences, wrote pamphlets and editorials and collaborated with them on the first few volumes of The Complete History of Women’s Suffrage. She was essential to the women’s suffrage movement.

“In history written by men, the women who most largely influenced the fate of the nation are but alluded to. Many women are almost entirely ignorant of the deeds of their sex in the past.” —MJG

Matilda loved to read and spend hours in libraries researching history, religion and other cultures. She developed a genuine connection with the local Native Americans, the Haudenosaunee. Matilda was able to share what she discovered from her research and experience: women’s lives weren’t always so constrained, women had accomplished things beyond housework throughout history, that women had a rich legacy that they should all know about it. I think the gift of this knowledge helped wake up her contemporaries and helped fuel their radical cause.

And her work is still shocking! One example from her 1883 article Woman as an Inventor that just slays me is about the invention of the cotton gin. We all “know” that it was invented by Eli Whitney. I remember learning that in High School History. At the time, Whitney was a boarder in the home of Mrs. Catherine Littlefield Greene, an impoverished widow with a plantation to run and children to support. Matilda suggests that the idea from the machine came from conversations at the dinner table, that it was Mrs. Greene’s idea, and that when the construction of the machine faced challenges, she was the one ready with solutions when Whitney wanted to give up (for example: she suggested using wire instead of wood to separate the seeds from the fibers). Though the product of her brain, the patent was taken out in his name because as a woman in “society” she would have been ridiculed for her participation in “industry.” That this might be true, that we don’t have the sources to support it, that we only know about it because of the writings of a woman, is the Matilda Effect in action.

It is important to acknowledge that the cotton gin had the tragic consequence of making the system of slavery “more sustainable at a critical point in its development.” Matilda, a lifelong abolitionist, abhorred slavery.

“We ask our rulers, at this hour, no special favors, no special privileges, no special legislation. We ask justice, we ask equality, we ask that all the civil and political rights that belong to citizens of the United States be guaranteed to us and our daughters forever.” —MJG

Long before Pussy Riot combined art and protest in a very public way, there was Matilda and the Suffs. One of their first major “stunts” with punk rock vibes took place in 1876 and Matilda was one of the participants. The scene: the centennial celebration in Philadelphia. It’s a hot July day but a crowd of thousands are gathered in Independence Square for celebratory speeches. The Suff’s request to speak had been denied, but Matilda—along with Susan B. Anthony, Phoebe Couzins, Sara Andrews Spencer, and Lillie Devereux Blake—decided they would not be silenced. They managed to get seats on the platform and in the middle of the ceremony, they stormed the podium and presented their rousing declaration that concluded with the words above.

I want to note that some of these women were in their forties and fifties when they did this and take a moment to appreciate how this “improper” and rebellious behavior delightfully contrasts with ideas we have of staid, disapproving Victorian matrons. Or even middle-aged women today.

“I regard the Church as the basic principle of immorality in the world, and the most prolific sources of pauperism, of crime, and of injustice to women.” —MJG

In addition to abolition and women’s rights, Matilda was also dedicated to preserving the separation of church and state. Though it was a radical idea at the time to talk about how the church’s teachings were the source of women’s subjugation, she wasn’t alone in her thinking. (I highly recommend the book From Eve to Evolution: Darwin, Science, and Women's Rights in Gilded Age America by Kimberly A. Hamlin, which outlines how Darwin’s theories helped further the women’s right’s movement by scientifically questioning everything people were taught by the church).

Toward the end of her life, Matilda sounded the alarm about conservative women joining the suffrage movement—led by Frances Willard and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union—some of whom were keen to get the vote for women so they could make Christianity the official religion. She understood that the hierarchy espoused by the church was fundamentally at odds with the equality that America promised.

I think of Matilda often when I doom scroll through the news and see an evangelical christian perspectives exerting their influence on the law. For example, the Dobbs ruling or what’s happening in Alabama. To which Matilda once eloquently said:

“My blood always boils at advice from a man in regard to a family. That, at least, should be the province of woman alone. To say when and how often she chooses to go down into the valley of the shadows of death, to give the world another child, should be hers alone to say.”

Matilda’s connection to The Wizard of Oz

In the summer of 2021, I took my young daughter on a road trip to visit a bunch of women’s historical sights in upstate New York (fun mom!). Our first stop was the home (now museum) of Matilda Joslyn Gage in Fayetteville. We had just stepped inside and I knelt down to tell my daughter “no touching!” But the museum guide interjected and said, “actually…she can totally touch stuff! The front parlor is full of dress up.” The front parlor was indeed full of…Wizard of Oz themed stuff! And lots of dress up. But why?!

When Matilda’s daughter Maud said she wanted to marry a struggling actor, Matilda and her husband forbid it. So Maud said she would run off with him, even if it meant never seeing her parents again. This story could be a tragedy, but then the Gage’s quickly decided love mattered more and they embraced Maud and her husband, Frank L. Baum. In her later years, Matilda lived with them and their children and she encouraged Frank to write down the stories he was always making up for the kids. Her philosophies and ideas are credited with influencing his book, The Wizard of Oz, about a girl who realizes her inner power and collaborates with friends to achieve her goals.

***

Like one of the 19th century women in the audience for Matilda’s speech on women’s history, I wonder “why don’t we know about this?!” Why isn’t Matilda Joslyn Gage more well known? The things she thought about, wrote about, spoke about and fought about are still vitally relevant today. There are a million little reasons why she and other important women from history aren’t more well known—who wrote the text books? Who decided what the curriculum should be? Who even thought to look for the women in history? We need to be like Matilda. Read, research, connect and collaborate, discover and put it all out there. Until we no longer ask “why don’t we know about her?!” Let’s put Matilda—and other women—back into the narrative.

Further exploring/reading/watching:

Check out the Gage Foundation and, if you can, I recommend a visit to the museum!

The Radical Feminist Behind the Curtain from Ms. Magazine.

Watch this very quick video about her life from PBS.

Thank you for this post! My 10 year old daughter and I did a week long road trip last winter break just like you and your daughter! We went to all the stops along the finger lakes to learn about suffrage, abolition, and native rights and culture. We also discussed intersectionality.

It sounds like you and I are equally fun moms! LOL!

We had never heard of Matilda before this trip, but she was the biggest hit! We loved her house and dress up. We were the only patrons there, so we got an amazing private tour and spent a lot of time there. She was definitely the coolest suffragist!

Now my daughter and I are putting together a booth for a Girl Scout event to teach other girls about suffrage. Guess who our main focus will be on? MJG!

It is also important that we bring forward the importance of Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglas in this struggle as they are not often included in our history books in this category.