In October of 1887, Nellie Bly embarked on the stunt that would launch her career: she feigned insanity, got herself committed to a notoriously vile insane asylum, and survived there for ten days. In the process, she exposed medical doctors as quacks and mental institutions as hellholes, she maybe had a flirtation with the one nice doctor and made some friends along the way.

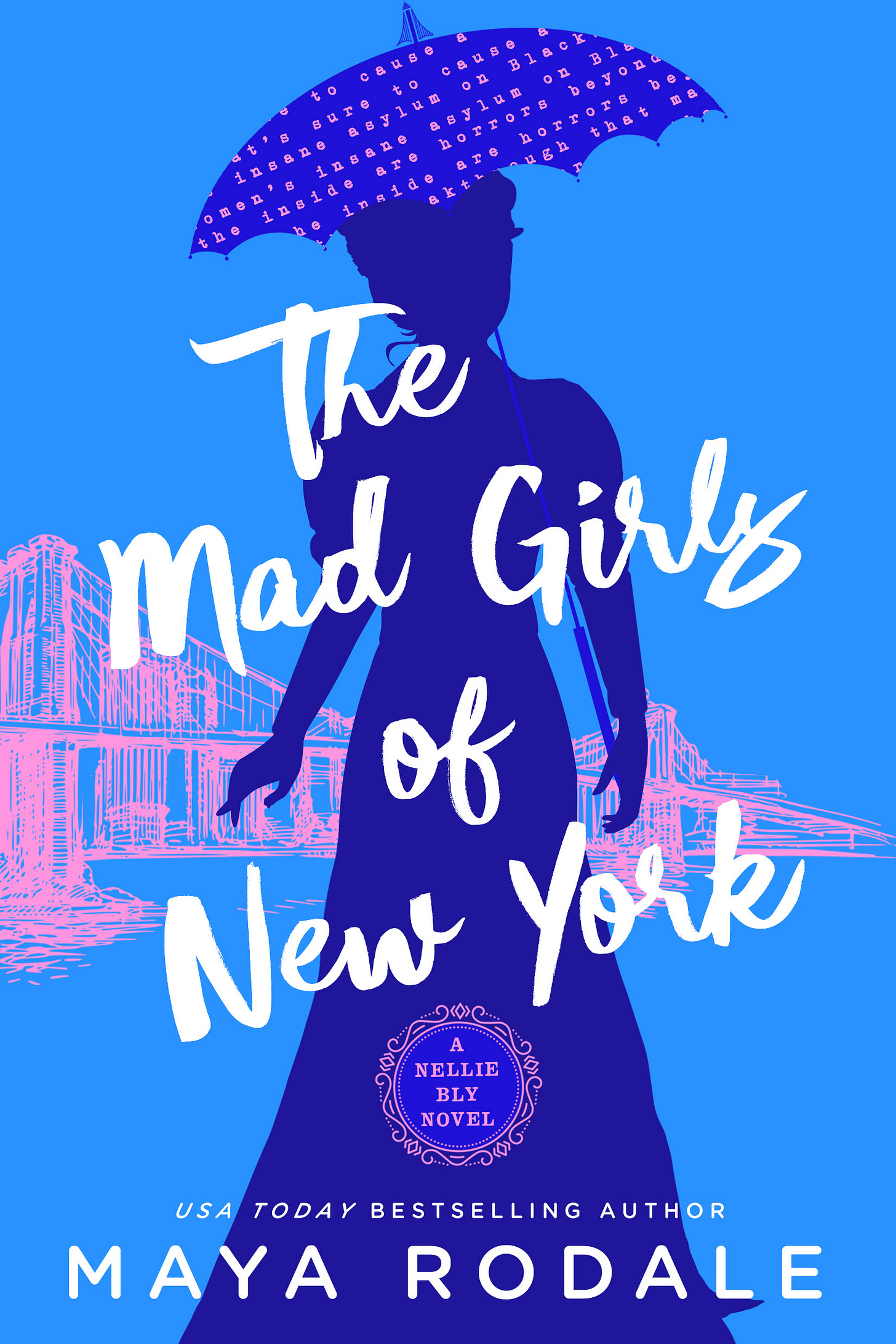

You can read all about it in my novel The Mad Girls of New York or Nellie’s original work Ten Days in a Madhouse. Today I’m thinking one overlooked part of this story—something even I hadn’t thought about until now.

One of the most horrifying aspects of the story is how Nellie gave up her insanity act the minute she was committed and no one noticed or cared that she was perfectly sane. This says a lot about how little doctors understood mental illness and women. They really had no clue. People then still believed in hysteria, the disease of the wandering uterus, which caused problems as it wandered around the female body. The supposed cure was marriage, having kids, and sex. This disease and it’s cure obviously false, but men believed it for a long time, probably because it was convenient for them to do so. Any annoying female thing could be diagnosed as hysteria.

It is also statement on how society then dealt with “difficult” women. Because Nellie wasn’t the only sane woman committed to an asylum against her will. It was apparently a done thing!

In 1860, Elizabeth Packard was forcibly committed by her husband for essentially questioning his authority and having her own ideas about God and religion. (Read more: the riveting book The Woman They Could Not Silence). There’s a story of Susan B. Anthony helping a woman escape an asylum after her husband put her there because she wanted a divorce. In her biography, Elizabeth Cady Stanton writes:

“Could the dark secrets of these insane asylums be brought to light, we should be shocked to know the countless number of rebellious wives, sisters, and daughters that are thus annually sacrificed to false customs and conventionalisms, and barbarous laws made by men for women.”

Of course, women with genuine mental health problems were institutionalized too. It is doubtful they got any actual care while in the asylums.

Nellie’s reporting called attention to all of this. Her exposé was explosive. Copies sold out around the city, investigations were launched, and reforms were instituted (though it took much longer to learn how to properly care for the mentally ill). At first I always thought the success of the story was because it was news to people that sane women were stuck in insane asylums but now I wonder if Nellie was giving voice to a long held suspicion folks held.

As I consider this story now, I think about what a society does with “difficult” women? I guess once upon a time it was witch hunts, or locking them in the attic, or dismissing and discrediting them by calling them hysterical or crazy so everyone can just ignore them.

This story also launched Nellie’s career and the practice of investigative reporting. Her stories almost always had a particular focus on the lives and experiences of working women. Whether she was exploring the black market baby trade, or working in a factory, or trying to get hired as a servant, Nellie put women’s stories on the front page. She and her work inspired dozens of other stunt girl reporters.

All these journalists showed the power of women’s voices because readers were insatiable for stories from the stunt girls. I think she and the other female journalists helped to make it harder to ignore and dismiss women. Part of the reason is because their stories sold a lot of copies and money talks. But the other reason is this: these stories humanized women and gave context to their lives. This made it harder to ignore, dismiss, or lock them away. I think it also gave women a sense that they deserved respect and attention.

As I’m writing this, I’m also listening to the new Stevie Nicks song, Lighthouse, (sent to me by reader Susan, thank you!) that reminds us all “don’t let them take away your power” which seems quite fitting. Let’s not be afraid to be opinionated, outspoken or silenced. I’m also in the middle of watching the Netflix rom com Nobody Wants This where the heroine, Joanne, is “edgy”, snarky, and afraid of sharing her feelings. And the hero is totally comfortable with that. I mention this because it shows another option of what to do with difficult, outspoken women: just love them.

Amen to that. Just love them. Isn't it shocking when we realize how deeply patriarchal attitudes, ideas, and behaviors are woven into our world as "natural" and "normal." It's one of those things, at least for me, that having seen unmistakable evidence of it, I cannot unsee it, and now, I see it in everything. At 66, my own long-standing feminism is undergoing renaissance, and stories like this one, Maya, help it keep going. Thank you.

this also happened in the 1970s, nearly 100 years later.