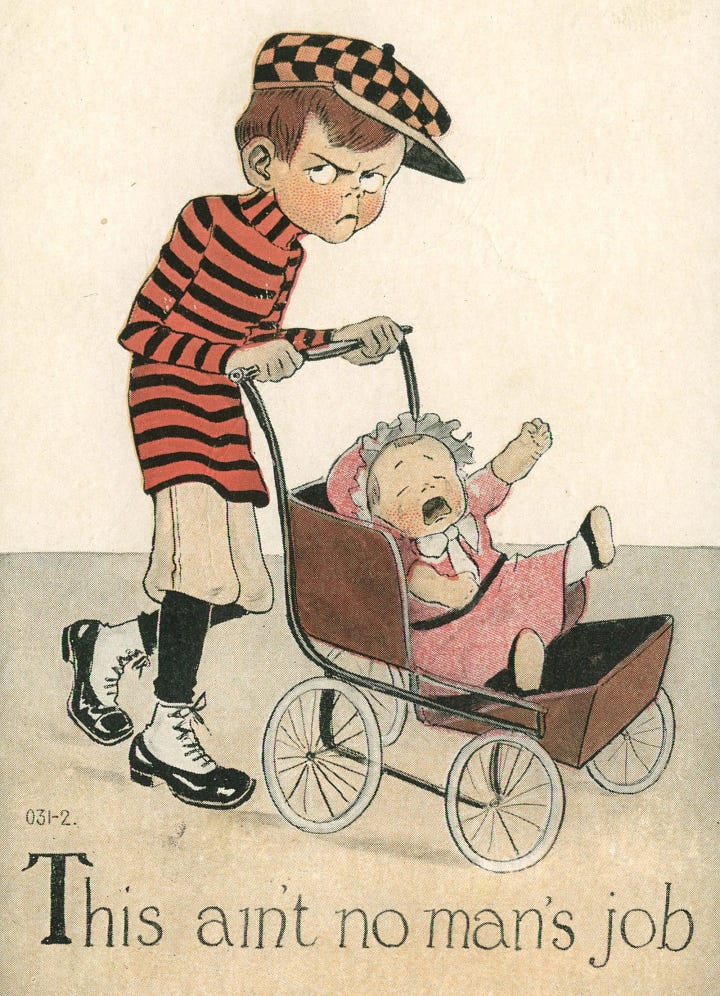

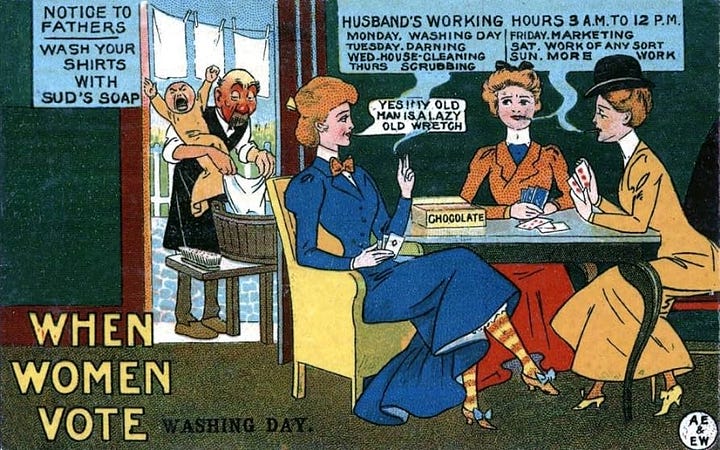

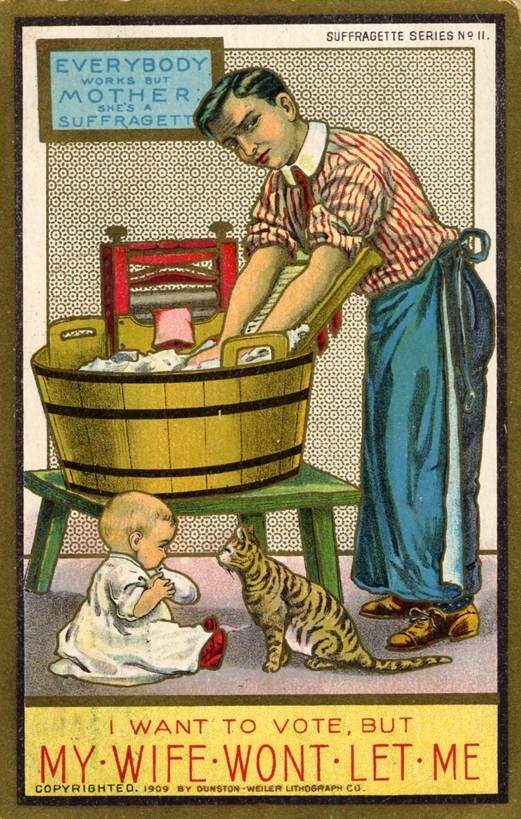

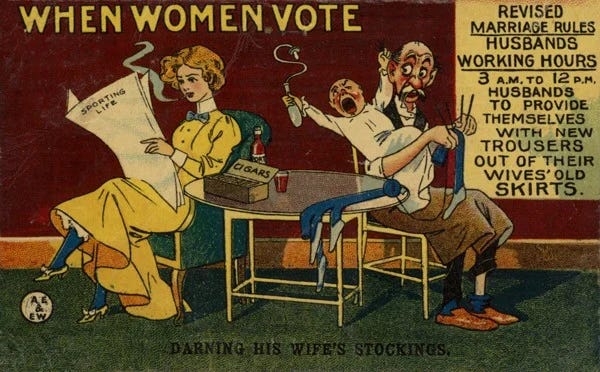

“Well, sir, I know that at the very mention of the political rights of women, there arises in many minds a dreadful vision of a mighty exodus of the whole female world, in bloomers and spectacles, from the nursery and kitchen to the polls. It seems to be thought that if women practically took part in politics, the home would be left a howling wilderness of cradles, and a chaos of undarned stockings and buttonless shirts.”

***

Although woman has performed much of the labor of the world, her industry and economy have been the very means of increasing her degradation. Not being free, the results of her labor have gone to build up and sustain the very class that has perpetuated this injustice.

—The Complete History of Woman’s Suffrage

There is no shortage of quotes about men’s fear that women would ditch marriage, motherhood and housekeeping if they got the vote. I have a very long list and those are just two. They also made cartoons about it. There are so many cartoons about the horror of men having to do their own laundry and watch their own children, should women get some political freedom. Oh no!

It’s haha funny—up to a point. Because tangled up in the notion of housekeeping are questions of freedom, equality, and the math which powers our entire economy. Basically, some people will do anything to get out of the necessary chores that get us all through the day—laundry for clean underwear, cooking food, cleaning up so we don’t fester in squalor.

A desperate avoidance of housework may have helped perpetuate slavery. In her book They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South, Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers writes that white southern women owned slaves and actively participated in this horrible system beyond just benefitting from it financially. In an age when the laws forbid women owning their own property, the exception seemed to be that white southern women who were able to own their own slaves. They weren’t passive owners either—they studied the market, attended auctions, bargained. The confinement that Northern women felt keenly—like the lack of financial resources to assure their independence, or at least leverage in their relationships—didn’t apply to these southern women in the same way.

A recent New York Times article about on the topic included this line that made a light bulb go off in my head:

white women may have also enslaved a higher percentage of Black women because they wanted workers in the domestic realms that they controlled, laborers who could handle cooking, cleaning, child care, sewing and other household work.

No one wants to do housework. They will enslave their fellow humans to get out of it.

Before we start clamoring about technology freeing women from household drudgery, a look at the history of housework reveals that it’s not that simple. In fact, many of the technological innovations for housework only freed men from their roles around the house—not women. Consider the cleaning of a rug.

In her book More Work For Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology From The Open Hearth To The Microwave, Ruth Schwartz Cowan details how this household chore changed over time. In yore times, house work was something a family did together. In spring, the men carried the rug outside, beat it clean and returned it to the house. This was a man’s job and it was done once a year. With the invention of the vacuum cleaner, it became a woman’s job and it was expected to be done on the regular.

This is repeated over and over again—with stoves, with laundry, with going to the mill. Technology freed men from housework so they could go work outside of the home, earn cash money and leave women stuck at home with the kids, increasingly high standards for housekeeping, and more to manage alone than before. Women were not happy. Cowan quotes one 19th century housewife:

“I am daily dropped in little pieces and passed around and devoured and expected to be whole again next day and all days and I am never alone for a single minute.”

When given the choice of housework as a domestic servant or literally anything else, most 19th and 20th century women chose literally anything else. It was a big problem for middle and upper class women who also did not want to do the drudgery of daily housekeeping. They lamented that all the immigrant women preferred to work in factories. While the hours in the factories were long, they at least ended and one could go home. Their free time was their own. They could have friends over, if they wanted. Being in domestic service, in contrast, meant living at work, being on call 24/7 with one afternoon off a week, and unable to gather with friends or family. In her book, Never Done: A History of American Housework, Susan Strasser writes:

“Despite the long hours, low wages, and unhealthful conditions of factory work, single women of the largely immigrant working class preferred it to housework. Women simply did not want to enter domestic service. Reformers reported not only a shortage of servants but the refusal of unemployed women to accept positions as domestics, although housework was a relatively well-paid occupation, especially since room and board supplemented wages.”

No one wants to do housework!

In the late 19th century and early 20th century we see the rise of Home Economics. This was an attempt to professionalize and legitimize housework by bringing researched-backed science to the work of cleaning homes, making clothes and feeding families. They talked about nutrition science, how to organize your kitchen efficiently, clean air standards and how to care for babies. When these women, as well as women in settlement houses who provided similar services, got to share their knowledge, lives were improved and even saved. The Home Economists did their best to show that housework was vital, necessary and a skilled occupation. But somehow, it didn’t make housework/mom work any more respected or compensated.

These days, we have all the tech support in the world, but we are more frazzled than ever. We have running water and electricity (yay!), but we also can’t just leave the kids outside all day with a sandwich and access to a stream. They need boxed mac n’ cheese that we have to remember to buy (but not in bulk, because then they won’t like it anymore) and an adult to stand at the playground with them and hold their water bottle.

Recent studies show that single, childless women today are happier than married women. Perhaps they see the amount of work involved in keeping house, maintaining family relationships (kids, husband, in-laws, etc), and taking care of children. They also see men and a society that won’t value this work, let alone provide any sort of help. Businesses have stepped up, with meal deliveries and cleaning services. Still, nobody wants to do housework and now women can opt out of doing it—at least for anybody else.

There are other ways off this merry go round, I think. They come from suffragist Elizabeth Perkins Gilman, who is best known for writing The Yellow Wallpaper. She also had some radical ideas on how to restructure society. In short: for people who loved childcare—be paid to give childcare! For people who loved housework—pay them well for it! For people who loved to cook—pay them to cook for all of us! We have approximations of this in the form of Amazon, food delivery services, cleaning ladies, and childcare if you can get it/afford it. But what isn’t properly valued is the work and expertise that goes into proving these vital services. This is what the Home Economists were trying to show us: it’s important work, based in scientific research, with real life consequences and it should be valued accordingly.

During the Quarantimes, my husband, toddler and I moved in with mom and sisters and it was an interesting experiment in housekeeping and childrearing. We very swiftly made a schedule for cooking meals and cleaning up after. Saturday was cleaning day, everyone got a job and everyone did it at the same time, with music. We each took an hour a day with the kid. And my work as a wife/mom/houselady was considerably lessened. We weren’t paying each other, but the work was so distributed that it hardly felt like work at all.

I actually enjoy cooking and cleaning. Sewing is my fun times hobby. But what I don’t like is feeling like my entire existence is serving others at the expense of my own interests. That’s what it can feel like when the workload falls entirely on one person in the house. The problem isn’t the work, it’s the way it’s not valued (in cold hard cash thanks) or equally distributed. Especially when this is the work that makes the world go round…and it is not accounted for! Our GDP, our entire economy, is running on bath math.

Nobody wants to do housework because no one wants to pay for it.

Consider this gem from the historical record:

The Legislature of Maine, after having granted nearly all other property rights to wives, found a bill before it asking that a wife should be entitled to what she earns, but a certain member grew fearful that wives would bring in bills for their daily service, and, by an eloquent appeal to pockets, the measure was lost for the time, but that which has secured other rights will secure this.

Entire systems were constructed to get out of paying for it—slavery, marriage in the patriarchy. From the Complete History of Woman’s Suffrage:

That in the general scantiness of compensation of woman's labor, the restrictions imposed by custom and public opinion upon her choice of employments, and her opportunities of earning money, and the laws and social usages which regulate the distribution of property as between men and women, have produced a pecuniary dependence of woman upon man, widely and deeply injurious in many ways; and not the least of all in too often perverting marriage, which should be a holy relation growing out of spiritual affinities, into a mere bargain and sale—a means to woman of securing a subsistence and a home, and to man of obtaining a kitchen drudge or a parlor ornament.

One glimmer of change: Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum recently proposed a pension for women, aged 60-64, in recognition of the unpaid work many of them have done for decades. Imagine if women were paid for the work they did to keep their families clothed, fed, clean, comforted, scheduled, etc, etc and so on and so forth. Imagine if governments had to account for it! Maybe if women were paid for it, then men would want to do it too—or at least be incentivized to share the load. After all, it’s work that benefits us all, every day.

I had to restrain myself from bringing Martha Stewart into this post, but a sequel would definitely be about how she is one of the very few women to make a f**cking fortune off of housekeeping and homemaking. She made it valuable. I think that's why there was a witch hunt to take her town.

Another post that it’s hard to hit the “like” button for, because there’s nothing to “like” about this except for your labor to pull the argument together. Kind of like housework in that sense. I personally am a man who enjoys household labor, particularly making dinner and doing dishes (so finite and accomplishable) and back in the day, having alone time with my sons to free Claire up to do Claire things. We ran wild in a Wolfpack! Your point about dividing and conquering is apt. Equal toilet cleaning under the law: if you use it, you need to help clean it. Is that so hard? Evidently yes, which is maddening.